There is a huge elephant in the room when considering crypto payments, and it seems like most people don’t see it. Whether you see it or not, it will have a massive influence on crypto payment systems.

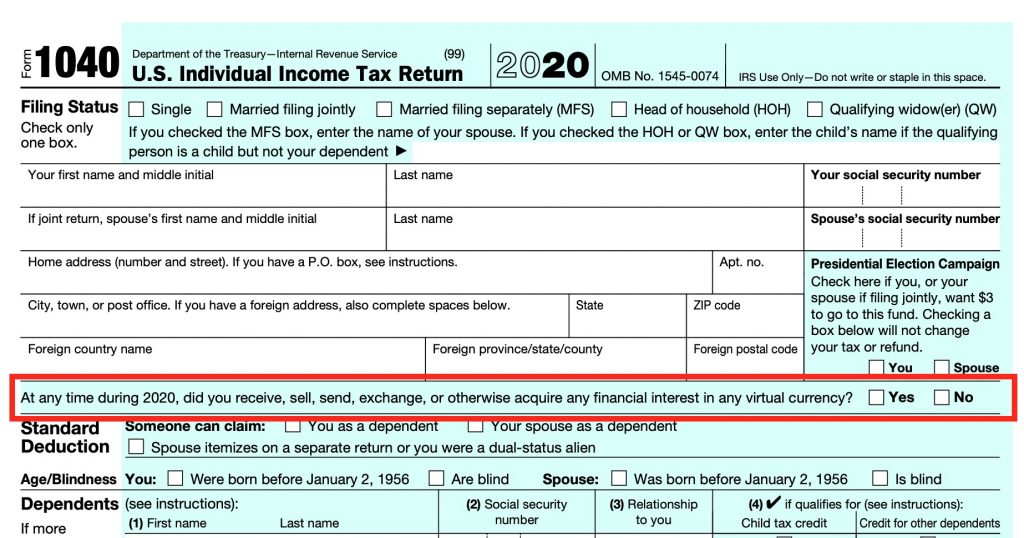

As cryptocurrencies become more widespread, and find their ways into more and more systems we use every day (such as Twitter’s recent addition of Bitcoin to its tip system), the implication of that elephant will become more widely understood. The elephant is that every time you spend cryptocurrency, whether by directly paying someone with it, or indirectly paying someone by using something like a crypto debit card, you are generating a taxable event. To be clearer, when you buy a cup of coffee at the neighborhood bodega with cash or a regular credit/debit card, you are not taxed for spending the money on the coffee. When you buy that same cup of coffee using cryptocurrency, you will be taxed on the money you spent (this assumes the value of your cryptocurrency has gone up since you got it, but even if it has not, you still need to report your coffee purchase in your tax filings).

How much? That depends on the local tax rules, but in most places you would pay the capital gains on the difference in cost of what you paid for that cryptocurrency. For example, if the crypto originally cost you $3, and it’s now worth $5 when you spend it, then you would pay your capital gains rate on the difference ($2) so if your capital gains rate is 20% then you would need to pay 20% of $2, or 40 cents. More importantly, you would need to have kept the proper records of when you bought and sold that cryptocurrency, know what the price was at each time in your local fiat currency, and know what expenses you incurred to make that payment.

In the above case today, you would have likely spent more in network fees than you did on the coffee, so you would have lost on the transaction, but you would still have to file it as a capital gain, although the cost of the transaction would probably prevent you from having to pay taxes on it. That also means the real cost of that cup of coffee was significantly higher for you than for the guy next to you paying cash, even before the tax implications. That’s another reason crypto payments haven’t taken off, although that particular problem will hopefully be remedied, either through the use of sidechains (like Lightning for Bitcoin) or through improvements to the blockchains themselves (such as Ethereum 2.0 when it is completed).

What crypto-related actions can be taxed? As mentioned above, simply selling your cryptocurrency, even $5 worth, and that’s a taxable event. Here’s an incomplete list of taxable events:

- selling cryptocurrency

- exchanging cryptocurrency

- receiving cryptocurrency, through mining

- receiving cryptocurrency, through staking

- receiving interest from lending cryptocurrency

- getting paid cyrptocurrency for goods or services provided

- getting paid salary in cryptocurrency

What crypto-related expenses can be used to reduce one’s tax burden?

- the initial cost of your cryptocurrency (which is used to calculate your gains)

- interest on money you’ve borrowed to buy cryptocurrencies

- transaction fees

- depreciation of capital assets (for businesses)

- mining costs (for businesses)

The key to all of this is an insane amount of bookkeeping. Businesses and independent contractors have long had to track all of their expenses, but most people wouldn’t think they would need to remember every cup of coffee they bought at Starbucks, and know be able to track when they bought the cryptocurrency they used to purchase that coffee, and record the transaction fees associated with those purchases.

Let’s take a look again at the coffee purchase. Let’s say you got lucky and bought 5 Bitcoins at $1000 each back in 2013. You’ve been HODLing them ever since, and now they’re worth $240K. You have a spanking new Crypto Debit Card, and want to start using it to pay for things. You go to Starbucks and spend $5 on coffee. What do you need to record for tax?

- Price of Bitcoin when you bought it ($1000)

- Date bought Bitcoin (Dec 1, 2013)

- Transaction fee from purchasing BTC

- Amount of Bitcoin spent (0.00010 BTC)

- Amount spent in USD ($5)

- Price of Bitcoin when spent ($47,990.10)

- Transaction fee from selling BTC

Now to calculate your taxes. You’ve held the Bitcoin for over a year, so you use the long-term capital gains rate to calculate your taxes. Let’s say your long-term capital gains rate is 20% (the current max in the US, although this may change). The $5 of BTC you just spent cost you 10 cents back in 2013 ($1000 * 0.00010 BTC), so your capital gains are $4.90. You could theoretically add the transaction fee from 2013 to your cost basis, although it was likely so low that it’s irrelevant. You’d also only get to do that once, so kind of irrelevant when considering buying coffee regularly. Your transaction cost to spend the BTC for the coffee, however, is more relevant. Today that might cost you under a dollar, which is lucky compared to mid-April when average transaction costs were over $50. Transaction costs fluctuate constantly and are calculated based on three factors – the cost of a satoshi (1/100,000,000 BTC), the number of bytes in the transaction (lets say about 250 for a simple transaction), and the current transaction fee, which fluctuates wildly, but currently is 7 satoshis/byte.

| Capital Gains | 20% of $4.90 | $0.98 |

| Expenses | 7 sats/byte * 250 bytes * $0.0004773/sat | -$0.83 |

Now we see that we have to pay $0.98 in capital gains taxes, but we can probably offset that with a transaction fee of $0.83. So presumably that would cost you only $0.15 in taxes, which is not so bad, although you actually paid $5.96 for your coffee, instead of $5 (about 20% extra), and you had to track all of the above details, and file them in your taxes.

The above is actually a simple example, since we assumed a single purchase of BTC, all more than a year earlier. What happens when you’ve been buying BTC regularly over many years, including purchases less than a year ago? And you’ve also sold BTC at various times over the years. Add to that many coffee purchases over the years. Each time you sell BTC you are incurring a taxable event, but moreover, you need to map each sale to a purchase in order to calculate taxes. If you have bought BTC 20 times, and sold it 100 times (smaller transactions obviously), then each piece of BTC you sell needs to be mapped to part of one of those 20 purchases in order to calculate the taxes on each sale. In addition you need to continue to track which parts of which purchase you’ve used to calculate your taxes going forward into future years, so you don’t use the same part of a purchase when filing different sales.

Is your crypto wallet tracking all of these data points? Is it able to generate a tax report based on the tax rules in your country? If not, can it provide those details to you in such a way to allow you (or your accountant) to generate your own report? Does it keep track of which purchases you’ve used to calculate capital gains, so the next time you generate a report, it doesn’t reuse the same purchases?

One might think we’re heading to a point where cryptocurrencies might actually be considered currencies, and make all of this obsolete. Just look at El Salvador which recently made Bitcoin legal tender in the country. As a currency of course it wouldn’t be taxed, but that doesn’t eliminate the transaction fees, which fluctuate so wildly that one day someone might pay ten times the cost of their coffee when buying it in just fees. Does the average consumer in El Salvador understand that? Can they afford it? And would El Salvador be a good example of things moving the right direction anyways? Do you know what the local currency in El Salvador was before adding Bitcoin? It was the US Dollar. Not an El Salvador Dollar, the US Dollar. El Salvador gave up dictating their own monetary policy twenty years ago and just adopted the US Dollar. Other countries, however, have a much stronger interest in preventing alternative currencies. China has been cracking down on Bitcoin usage, with limited success (as illustrated by the fact they’ve banned Bitcoin transactions multiple times since 2013). The US isn’t really interested in providing a way to circumvent their monetary policy either. While it doesn’t look like the US is interested in banning Bitcoin, it definitely does not consider it a currency and has no plans to make it into one.

This all goes back to the old argument if Bitcoin is a store of value or a means of payment. As long as each sale requires tracking at least a half dozen data points, and continuing to track them for years, it will be complicated to use it as a payment system. If transaction fees are reduced to where they are irrelevant in making a purchase, and countries begin to recognize it as a currency, it may start to be usable as a means of payment, but until that point it’s primarily useful as a store of value. The most important factor that needs to be overcome in making cryptocurrencies useful for payments is making it dead-easy to do, so anyone can do it, and not risk losing money while doing it (by not realizing, for example, that a transaction fee cost more than you spent). Reducing fees will help that aspect, and improving the user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) will help even more.